Story Devices in Computer Games

At the same time, Valve laid down other foundations that are still being expanded upon – the idea of a silent, (and possibly unwilling) narrator is one that’s hard to explore in literature, but very much suited to games.Valve weren’t the only people interested in these ideas obviously, which is further proof that the changes in design and plot approach were industry-wide. Ion Storm, for example, were playing with the idea of giving players false information in Deus Ex at around the same time, contrasting the free-form gameplay that formed the backbone of the game with the player expectations that ‘I am the good guy’.

The brilliant climax of all of this occurs when your boss, Anna Navarre, orders you to kill the unarmed ‘terrorist’, Juan Lebedev. The first time you play the game it’s impossible not be hit by panic and confusion as you ask yourself what you’re supposed to do. I'll freely admit that, even though I know the game back to front and always play with a particular style and plan in mind, I always get hit by indecision at that point, sometimes overwhelmed by the implicit question - what is the right thing to do?

Look at you, Hacker; a pathetic creature of meat and bone, panting and sweating as you run through my corridors.

System Shock 2 plays along similar lines at points with an unreliable narrator, but it’s BioShock that really shows how far games are able to build an entire plot to play off the player assumptions. While Deus Ex was interesting because it gave you a choice in a situation where you assumed there was none, BioShock’s story is about being a slave in a game that’s all about freedom. Compare any of these ideas to the whatever supposed themes are to be found in Quake or its kin and it’s clear that the way games use and abuse stories has come on in leaps and bounds.

Nor is any of this limited just to first person shooters either – similar observations can be made of almost any other genre. Survival Horror games were probably the quickest genre of them all to improve the stories they tell, going from Resident Evil’s simple ‘zombies in a mansion’ plot to Silent Hill 2’s symbolism-soaked story about mourning, guilt and hurting the ones you love in less than five years. It’s just a shame nothing has yet topped SH2.

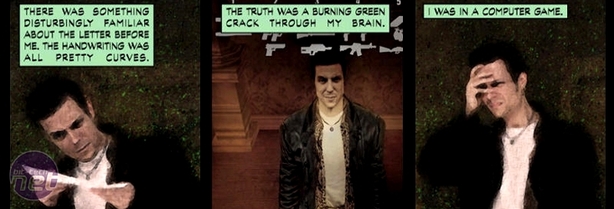

Likewise, third person shooters underwent a series of revelations and expansions – Tomb Raider was an excellent game but story-wise it was always as fake as Lara’s famous assets. Max Payne on the other hand showed what you could really achieve with the genre if you were willing to get your hands dirty though, weaving a grim and oppressing plot that flew in the face of what Tomb Raider stood for.

In fact, the changing demands and growing popularity of third person shooters eventually forced Tomb Raider to re-invent itself to stay relevant, casting Lara not as a millionaire adventurer but more as a scarred and traumatised young woman. Desperate to stay with the current fashion for flawed heroes, the series looks to reimagine itself again soon. Likewise, the long-running Resident Evil series is moving closer to the third-person shooter genre with every iteration – the ideas and themes of those earlier games just aren’t as gripping to current audiences, it seems.

The adventure and RPG genres haven’t been left out in the cold either. The adventure games of the early 1990s were nearly universally based around parody or comedy settings, with LucasArts’ Monkey Island being one of the most well-known titles in the series. Monkey Island is especially interesting as it came from a deliberate attempt to create a new trend, with Ron Gilbert and Co. often saying they were desperate to get away from the fantasy settings of previous adventure games. Sierra’s King’s Quest had become old-hat and Monkey Island was a deliberate (and successful) attempt to replace it with a new type of adventure game.

Adventure games as a whole have arguably struggled to stay as popular as they were back then though, with companies having to adopt new structures and pricing models to keep what we inevitably now think of as old-fashioned adventure games going. While comedy adventures are starting to make a comeback, there’s also a growing number of adventures that can’t be easily classified, from Grim Fandango and The Longest Journey to Nikopol and Myst. Their very existence is proof that adventure games are trying to mature and grow into something that doesn’t have to be funny, perhaps held back by the need to be profitable – which probably explains why so many indie adventure games are starting to ignore the humour route in favour of more cerebral themes.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.